Thirty years ago, an earthquake desolated the San Fernando Valley. Buildings were destroyed, locals were devastated and California State University, Northridge crumbled. With community efforts, though, the college quickly recuperated and was soon up and running after a month.

A monument was later erected by CSUN’s then-President Blenda Wilson, who was hired in 1992, to commemorate and acknowledge the faculty and staff of the university, but a crucial part was missing — a dedication to students who put in the extra effort and time to volunteer.

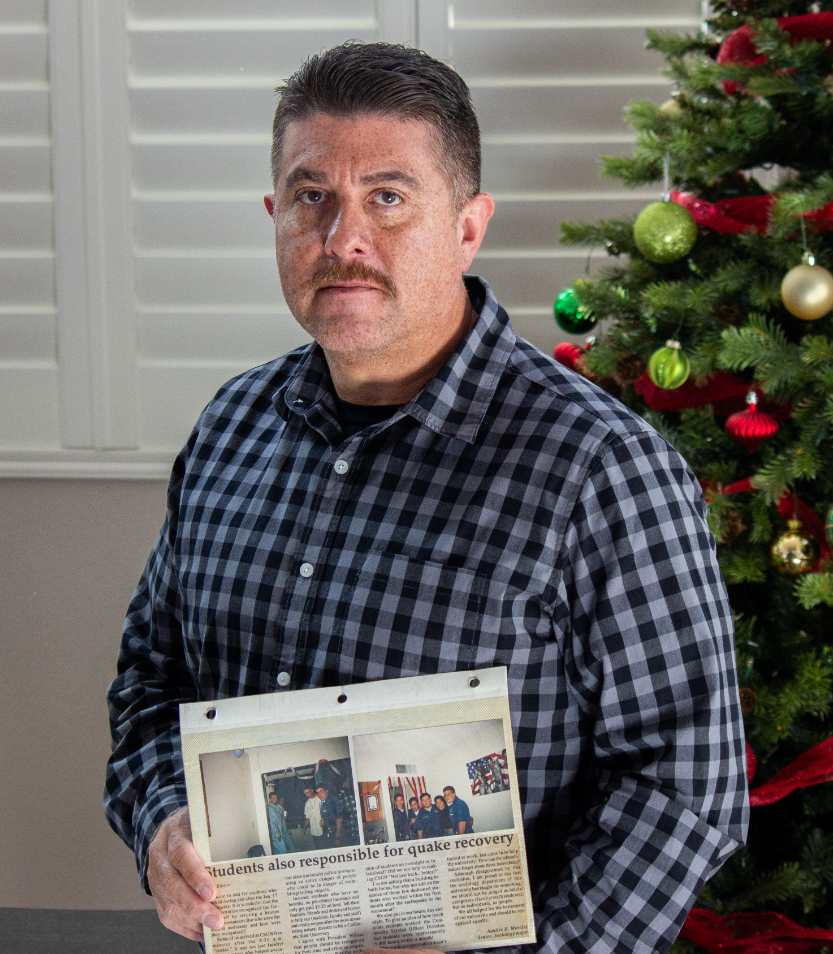

During his undergraduate studies, CSUN alumnus Aquiles Morales worked as a community service officer and student volunteer. In partnership with the campus police services, Morales and other student volunteers dedicated time to assisting the campus and the community with anything needed after the earthquake.

Morales was living in an apartment on Reseda Boulevard and Prairie Street at the time. He said the surrounding area had been wrecked.

“Everything around where I lived was pretty badly damaged, and it was pretty scary,” he said.

Morales, who was studying sociology, said that the earthquake heavily impacted the community and left students in uncertainty.

“The campus that I knew when I first got to [CSUN] and the way that it was had completely changed,” Morales said. “I had classes in Sierra Hall and they were pretty damaged, so we couldn’t go in. As students, it really impacted us because we had to adjust to being in makeshift classrooms.”

Bungalows were put in place of classrooms, but because the earthquake happened in January, students had to weather rain and mud to continue attending class.

“Because that happened in January, you go through a season of winds, cold and rain, and that January it really started to come down,” Morales said. “A lot of the areas where these bungalows were set had a bunch of dirt and grass areas, so we had to walk through a bunch of mud too. It was pretty nasty.”

After the campus had more or less been restored, Morales said the monument Wilson presented a year after the earthquake felt like a slap in the face. It only mentioned the faculty and staff who helped the university, but not the students who volunteered just as much time.

“We dedicated a lot of our own time too, not just our school environment where we were trying to learn what we were going to school for, but at the same time we were working,” Morales said. “I felt a little betrayed by my school, but particularly by the school president, because I would’ve thought she would’ve also acknowledged the students on the plaque.”

In response, Morales felt like something needed to be said and that the students needed to be recognized in some capacity for their efforts, so he wrote a letter to the editor at The Daily Sundial and Wilson to express his frustrations with the lack of acknowledgement. He suggested students should have at least been added to the plaque.

“I’m not asking that a building be built for us, but why not add on the names of those few dedicated students who worked within the first month after the earthquake to the monument?” his letter read. “We all helped for the betterment of our university and should be recognized equally.”

Shortly after, Morales received a letter in the mail, handwritten by Wilson. She apologized for not including students in the plaque, but added that her reason was because the faculty and staff would be at the university for more years to come.

“I felt like that was a slap in the face, with all honesty,” Morales said. “I thought, ‘Well, okay, I get it. They’re working there and may be for the next few years, but I’m going to be an alumni. Is that not anything important?’”

He added that while he was not trying to discredit the efforts of other faculty members, he felt the recognition was unbalanced.

“I honestly don’t remember faculty members, beyond maybe the police officers and maintenance people, being on the campus because it happened so early in the morning and it was a Monday,” he said. “There were some of us that were there literally right after it happened, like, within an hour or two.”

Morales also received a letter from then-chair of the sociology department Harvey E. Rich, who thanked him for his work as a community service officer.

Even now, Morales said he still reflects on what he experienced and how the ordeal left an indelible mark.

“It was something that happened, and I still understand the passion I had then about what happened to now,” he said. “I still feel the same.”