For a community to rise, everyone must contribute.

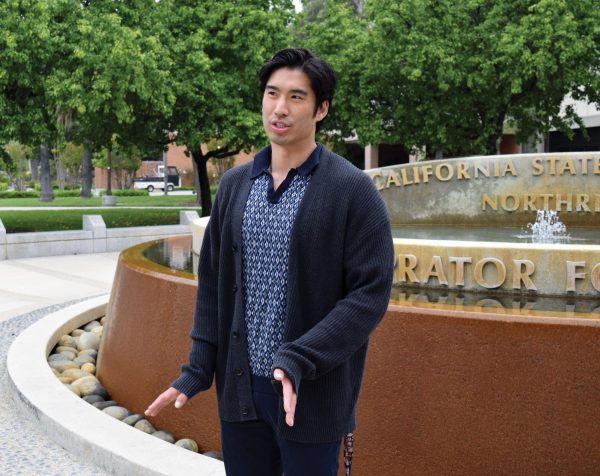

Dr. Joshua Chow, a post-doctoral counselor fellow at California State University, Northridge’s University Counseling Services, champions this idea and contributes through his work as a psychologist. The Chinese-Taiwanese counselor works with people of all backgrounds empathetically and humbly as informed by his learned experiences.

Chow finds beauty in the work he does and often paints pictures in his head of his experiences. When speaking about the societal pressures people face, he pictures a box that illustrates a feeling of constraint.

“I think of it like society is trying to put them into this tiny box they don’t fit into,” said Chow. “Once therapy starts to open the box, this huge rush of beautiful colors comes out.”

Chow’s father was born in Taiwan and moved to Hawai’i when he was 8 years old, and his mother was born in Oakland. Coming from a family with intersecting cultures, Chow was immersed in language and cuisine until things changed at a young age.

“My parents were very focused on making sure we fit in,” said Chow. “They were worried about what others would think of us.”

Intense assimilation is a common experience of Asian Americans, especially children of immigrants, according to a 2024 scholarly article in the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. The article delves into the paradox of Asian American assimilation: Asian Americans are the fastest-growing ethnic minority in the U.S. with large buying power despite a history laced with racism and exclusion, which were perpetuated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Many families encourage their children to eat “white” food and participate in hobbies associated with whiteness to fit in and avoid being othered based on their ethnicity. Taking on these markers of the majority is meant to benefit the minority, but it can negatively impact one’s view of themselves.

“There was a lot of internalized racism there,” said Chow. “I used to want to be white so bad growing up.”

While in the throes of teenage self-discovery, Chow found passion in helping others. In high school, Chow worked with students in Special Olympics to support them in their athletic journeys, which served as a leaping pad for him to pursue a life of advocation and service for others.

“It was so wonderful to see the effects it had on people, even when I was 16, 17, 18,” said Chow.

The transition from high school to the University of California, Davis was a major turning point in Chow’s life. Through the communities he interfaced with and lectures he attended, his relationship with his Asian ethnicity evolved.

“That started to change in college,” said Chow. “I started to discover there is beauty in being Asian, and I would not want to be white at this point.”

The path to self-acceptance and empowerment of one’s Asian identity is unique to each person, and has been explored in numerous best-selling memoirs, including “Crying in H Mart” by Michelle Zauner and “Minor Feelings” by Cathy Park Hong. A resounding theme from works focused on identity is the difficult path one treads to reach acceptance.

In university, Chow double-majored in psychology and evolution, ecology and biodiversity, which led him to research the latter field straight out of undergrad. While he found the research interesting, the process lacked the human interaction off of which he thrives, so he shifted his trajectory to psychology.

Chow’s switch brought him to work with people in need at Maitri Compassionate Care in San Francisco, which provides care and resources to people living with HIV/AIDS, as well as people recovering from gender-affirming surgeries.

In his time at Maitri Compassionate Care, his passion for helping others solidified.

“It’s not even satisfaction, it’s higher than that,” said Chow. “Finding my purpose in life through that.”

He also recognized the importance of working with people with marginalized identities, who are often left out of conversations of mental health.

“I want to work with these folks,” said Chow. “In actuality, work with people both similar and different to me, but still sharing these identities.”

Working with people living with HIV/AIDS reminded Chow of the recency of the ‘80s epidemic. HIV/AIDS can affect anyone, but the disease remains heavily associated with the LGBTQ+ community. Since the disease became common knowledge, it has been used to stigmatize queer people with some labeling it “God’s punishment” for gay men, according to a 2002 scholarly article from the Journal of Medicine and Philosophy.

While working at the care organization, Chow realized his understanding of ancestors differs from the widely accepted definition.

“Oftentimes, there’s an assumption that ancestors mean my direct bloodline,” said Chow. “Through working with these folks, I learned truly that we’re all connected. The people who experienced the HIV/AIDS epidemic are my ancestors. I do stand on their shoulders today for what they had done and what they sacrificed, oftentimes not willingly.”

Chow went on to explain how his view of ancestors and their sacrifices inform his life.

“Everything that they’ve done has added up,” said Chow. “It collectively has made me who I am today but also has given me privileges that they certainly did not have. I hope to pass that on to future generations through the work that I do here.”

As a queer man, Chow highlights the importance of knowing one’s history to be in touch with one’s identity. He began his coming out journey in freshman year of university by telling his friends and waited until after graduation to tell his parents.

“I was privileged to have a family who I knew would be there and would not abuse me or neglect me after I came out, and still, the worries were there,” said Chow.

Coming out is a daunting prospect for people from all communities. Queer Asians are noted as repressing their sexuality to avoid stigmas in their families and lives, according to a 2014 scholarly article in the Journal of Men’s Studies.

The HIV/AIDS epidemic still affects how people see queer identity, even among people they know.

“When I came out to my mom, I think that she was quite scared, and I sort of didn’t understand that at the time,” said Chow. “It was through working with (people living with HIV/AIDS) that I realized, ‘Oh, this wasn’t far away at all.’”

As Chow went into a doctoral program at the Wright Institute and moved into new workplaces, he maintained his reverence for the community he gained at Maitri Compassionate Care.

“I get the opportunity to support them when they were supporting me without even knowing it before I was born,” said Chow.

From his upbringing in an Asian household to working with people living with HIV/AIDS, Chow grew to champion intersectionality and the unique ways people’s identities inform one another.

“I am super grateful for my queerness because that is the venue through which I was able to find love for my Asian identity,” said Chow. “I started to learn that being different was actually really powerful.”

Not every Asian person is the same despite perceived phenotypic similarities, and their experiences are tailored to them based on their identities. Chow’s understanding of this allows him to be open in every counseling session at UCS, where he works now after varying positions throughout his doctoral program.

“Everyone is their own individual, unique person,” said Chow. “It helps me to have a lot of empathy for people who have different and similar experiences.”

As a post-doctoral counselor fellow, Chow works with students from all backgrounds with clinical interests in marginalized minority groups and people who experienced trauma. He also holds Let’s Talk sessions at the Glenn Omatsu House, which are informal opportunities for students to meet counselors and learn about UCS.

“Let’s Talk was a way for me to show students, ‘Hey, there is representation here,’ and ‘hey, we’re not that scary,’” said Chow. “That’s one of the things I love about UCS. We really are trying to be our most human being selves here.”

As reflected by other Let’s Talk hosts, including Marlon James Briggs who holds sessions at the Black House, it is helpful for students to see counselors face-to-face and be exposed to the diversity of UCS. In the conversational setting, counselors can break down preconceived notions of therapy and work with students to help them reach their academic and life goals.

“With all that stigma we hear as Asian people, it takes a little bit of time and energy to allay people’s fears of what counseling can be,” said Chow. “Sometimes it takes a similar face or someone who holds similar identities to calm that fear down.”

Chow expressed happiness in his work at CSUN with students being the highlight of his job.

“The students who I see are very grateful, and that is something that is very special about this place,” said Chow. “When they come and seek services, they are so lovely and so willing to engage in growth.”

Helping people of all backgrounds with his skills is the basis of Chow’s drive. His life’s mission is predicated on collective liberation, which states everyone plays a role in oppression and can transversely play a role in dispelling oppression, according to an article from The Assembly, a journal of education at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

“In order for myself to gain freedom, I need to be able to advocate and fight for those who don’t have that,” said Chow. “Therapy is one of the ways I am able to do that.”