No one knows giant monsters and machines like the Japanese.

However, America appears to be scooting its way onto the shelf with remakes like the “Transformers” series and the upcoming “Godzilla” film. Granted, these were imports, but the success of more original concepts such as “Pacific Rim” and the recent “Titanfall” video game show that there is a market for these genres domestically.

This might be the mentality behind one of the most recent and subtly popular imports, “Attack on Titan.”

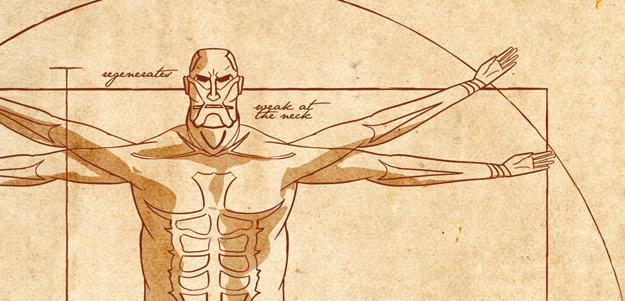

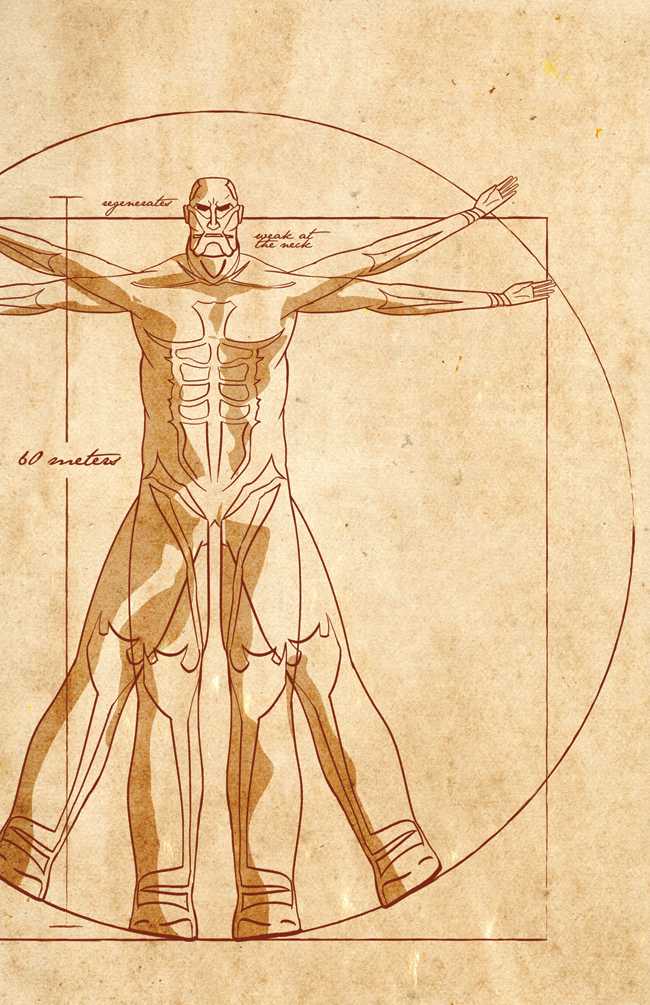

In the animated series, humanity falls victim to titans, giant humanoid monsters with mysterious origins and an insatiable bloodlust for humans. These goliaths straddle the kaiju and mecha genres of science fiction in a whole new way.

For the uninitiated, kaiju films (translated from Japanese as “monster”) center on giant creatures that characteristically wreak havoc on humanity, often with a preference for densely populated cities. Classics such as “Godzilla” and “King Kong” exemplify the genre with “us versus them”-type conflicts and what we shall kindly call “creatively resourceful” special effects.

Mecha stories feature equally large robots, sometimes with an internal human operator. These machines are more prevalent in Japanese anime, like “Gundam” and “Neon Genesis Evangelion,” than they are in America. With mecha built both for and against the main protagonists, stories usually climax with an epic robo-showdown between good and evil.

When these two genres intersect in the traditional sense, you get monsters versus mecha, as was the case in last year’s “Pacific Rim.” When concrete walls failed them, humanity answered its leviathan problem with mecha of similar proportions to give the monsters a good old fashioned beat down. The film made over $100 million in the box office domestically.

In “Attack on Titan,” civilization retreats from the titans behind a series of walls, which start to crumble after 100 years of relative security. The onslaught that follows is brutal. Instead of building robots, a handful of our medieval heroes discover a dangerous power within themselves, allowing them to combat the titans on equal terms. While avoiding imminent death, the protagonists face more sinister villains and deeper truths.

The anime arguably draws from both genres. By turning the kaiju, or titans, into controllable, piloted weapons, the lines are blurred. A select few humans, known as titan shifters, can create, but are separate from their titan bodies, which can be destroyed and regenerated, generally without effect on the shifter. Shifters aren’t scaled up to be titan-sized — they physically form a titan to fight in.

“Attack on Titan” is similar to “Neon Genesis Evangelion,” in that its pilots are biologically hardwired into their fighters, resulting in organic, internal control. These contrast the usual independently sentient beings that define the mecha genre, like the robots from the “Transformers” series.

While these concepts are by no means original, the skillful twist that “Attack on Titan” has put on them makes them freshly palatable for an American audience.

In an interview with a Japanese news outlet, the creator cited fear of an aggression that can’t be communicated with as inspiration for his titans. Indeed, the monsters aimlessly and violently eat humans with no apparent purpose. This theme echoes the original kaiju, Godzilla, whose only character trait was destruction. The consciousness and purpose that titan shifters introduce to the story is characteristically mecha.

Themes aside, the art goes beyond the flat colors and lines that make up most anime. Instead, producers opt for atmospheric lighting that borders on theatrical, as well as character design and development that eschews traditional anime tropes. The story is set somewhere in rural Europe where isolation has caused time and technological advancement have come to a stand-still. Even if you make a point to avoid Japanese animation, this one is worth a watch for its visual effects alone.

Having started as a manga in 2009, the book series is much further ahead than the anime, which wrapped up its first 25-episode season last fall. Rumors say the studio is waiting for more content before the show resumes, but with chapters published monthly, it may be another year before a second season is even confirmed.

In the mean time, Cartoon Network’s recently revived Toonami programing will start airing the show this Saturday, but all 25 episodes are available on Netflix streaming. An English dubbing is set to be released in two parts this summer. In Japan, a live action movie is slowly coming together for release in the near future.

As the semester wraps up, this is definitely one to make a summer must-watch series. We suggest starting after finals though, because once you start, you’ll be hooked.