With only half an hour to collect their belongings, Eva Brettler, her grandmother and her aunt were told that they would be taken to a concentration camp.

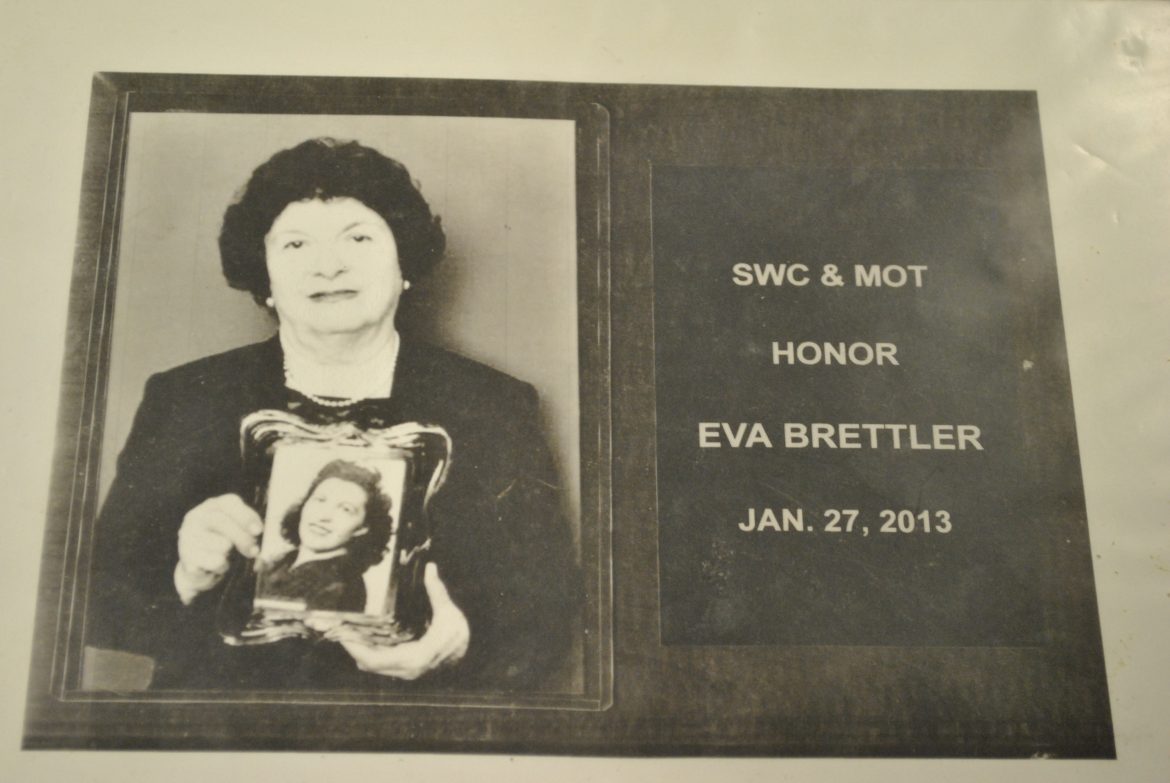

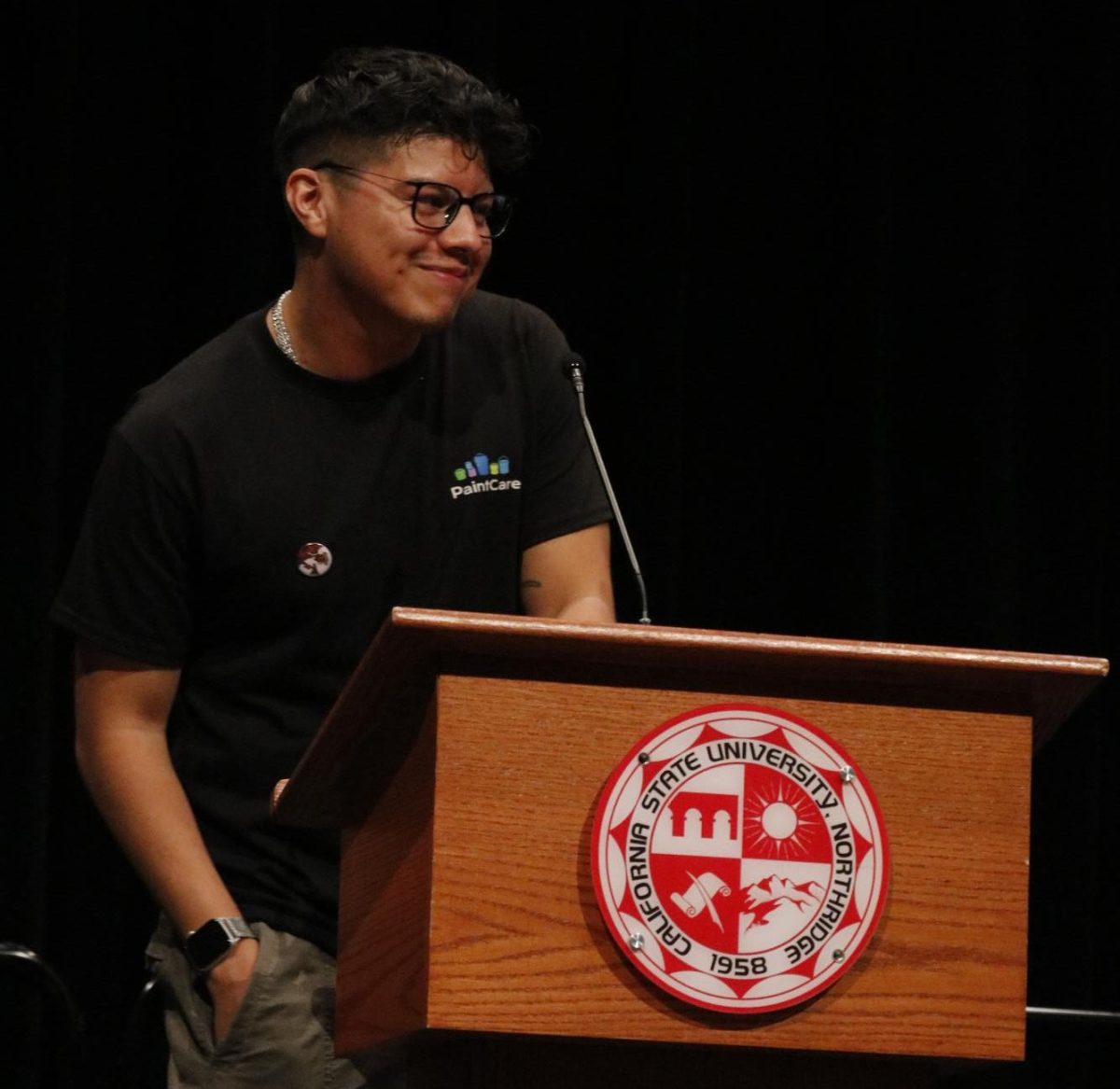

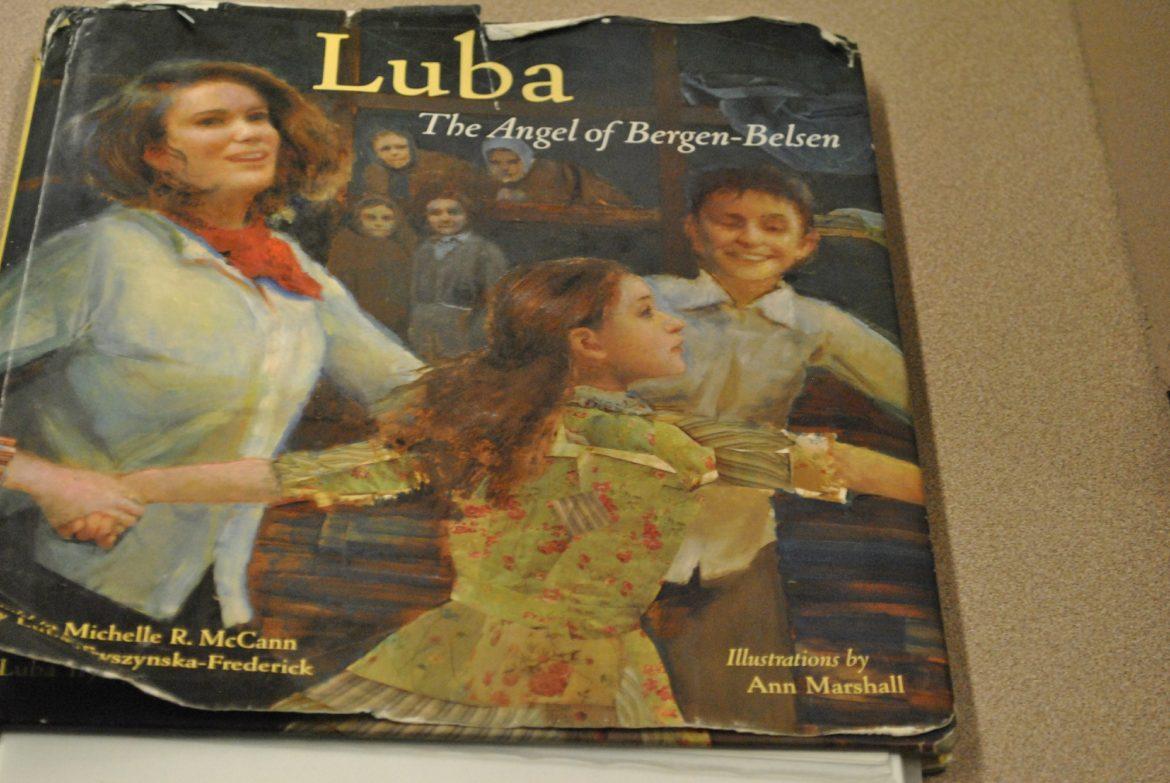

Brettler, a survivor of the Ravensbruck concentration camp, spoke to CSUN students about her experience before, during and after the holocaust.

“One day, my grandma was baking bread and suddenly there was loud banging on the door,” Brettler said. “Two Hungarian policemen came in yelling at my grandmother and aunt. They said ‘you have half an hour to collect some of your belongings before we take you to a concentration camp.’”

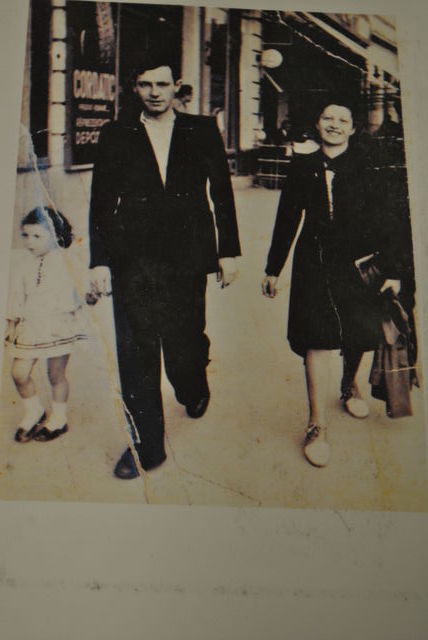

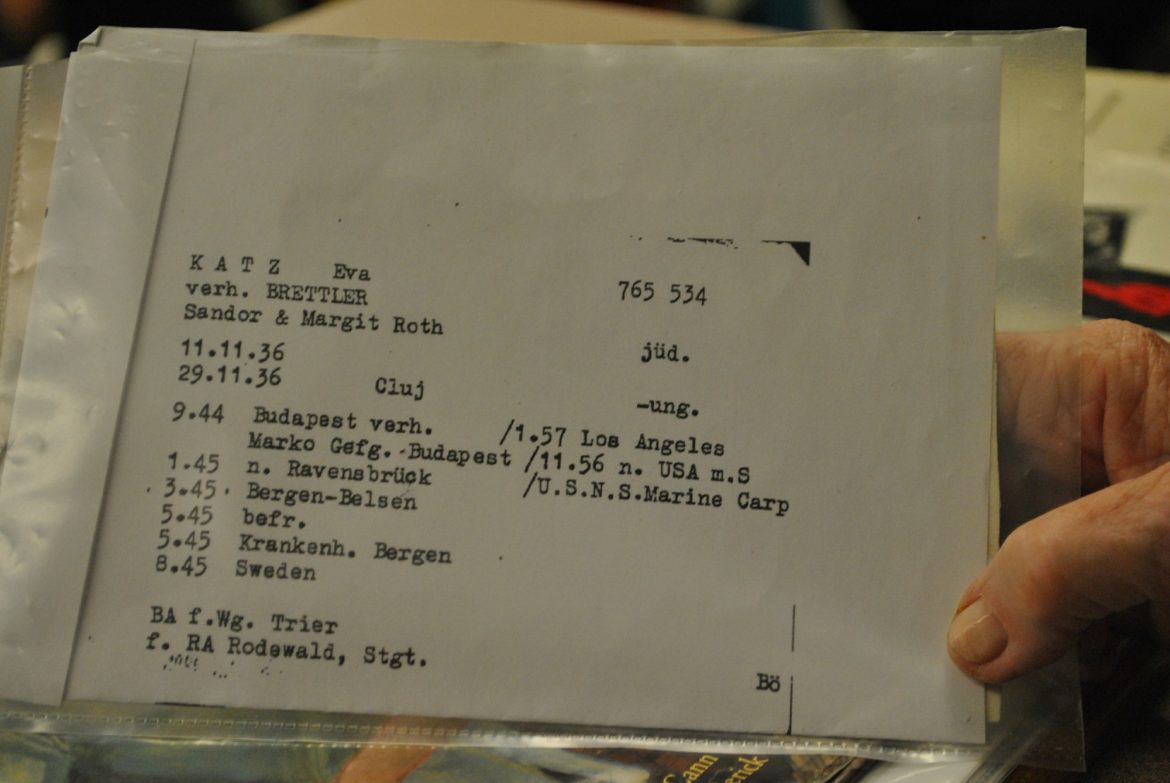

Brettler was an only child to Sandor and Margit Katz. Her father worked for a printing company and her mother was a hat maker.

“I was four years old when my father lost his job and we had to move to Budapest,” Brettler said. “We left everything behind.”

When Brettler was at her grandmother’s house, soldiers came with orders to take her family.

“My grandmother said ‘Your name is not on the list,’” Brettler said. “’I want you to hide in the cornfield and when the evening comes, go stay with the neighbors. I want you to live.'”

With little food, she hid and watched as her grandmother and aunt, along with other Jews, were led away by soldiers. Once night fell, she went to her neighbor’s house.

“I lost grasp of time soon after that and didn’t realize when my father arrived to get me,” Brettler said. “My father had me pretend I didn’t know him by making me walk ahead of him, because he had a star and I didn’t.”

The next day, her father was released and they left to the train station.

“My father approached a random woman with a child at the train station and asked her if she could take me on the train,” Brettler said. The woman agreed even though taking care of a Jewish child was dangerous because she could have been arrested, according to Brettler.

On March 19, 1944, the Germans officially invaded Hungary. By April, Brettler said her apartment had to be Jewish-free.

“My mother and I then moved to a safe house,” Brettler said. “One day my mother put me in a wicker basket, put towels over me, and placed me on top of furniture. Meanwhile, she hid in an elevator shaft.”

Soon after, the two left the safe house and her mother changed her name. Under her new name, Brettler was enrolled into school, but was then arrested and taken to a concentration camp.

Brettler’s mother was 28 when she was killed in the concentration camp.

“One day, my mother’s feet were bloody and then she took me to a wagon,” Brettler said. “They let me on but took her away. Soon after I heard gun shots. That evening every time the door opened, I hoped my mother would walk in but she never did.”

Brettler recalled a strip-down process that prisoners of the camp had to follow.

“When you arrive, they have you strip down,” Brettler said. “All I had left was a ring that I got for my seventh birthday. I was so desperate to have something that connected me to my family so I quickly hid it under my tongue.”

Brettler said that one of the lessons she learned was to never give up and to keep praying.

On April 15, 1945, Brettler was liberated from the camp by British soldiers. Soon after she was freed, but was diagnosed with typhus, the same illness that killed Anne Frank. However, Brettler was fortunate to be treated outside of the camps.

“I ended up in an orphanage on July 1945,” Brettler said. “By then I had lost track of time and even forgot my birthday. I began to consider the day I was liberated, my birthday.”

Two years later, she was pulled into the principal’s office and was told her dad was alive.

On January 1947, she met up with her dad who had remarried and had a son.

“I had forgotten my native language but luckily my father had learned many and we were able to communicate,” Brettler said.

On October 26, 1956, the Hungarian revolution motivated Brettler to leave Hungary. Through a detour, she ended up in Vietnam. Then on January 1957, President Eisenhower granted refugee to those who had specialized in certain fields, and Brettler qualified.

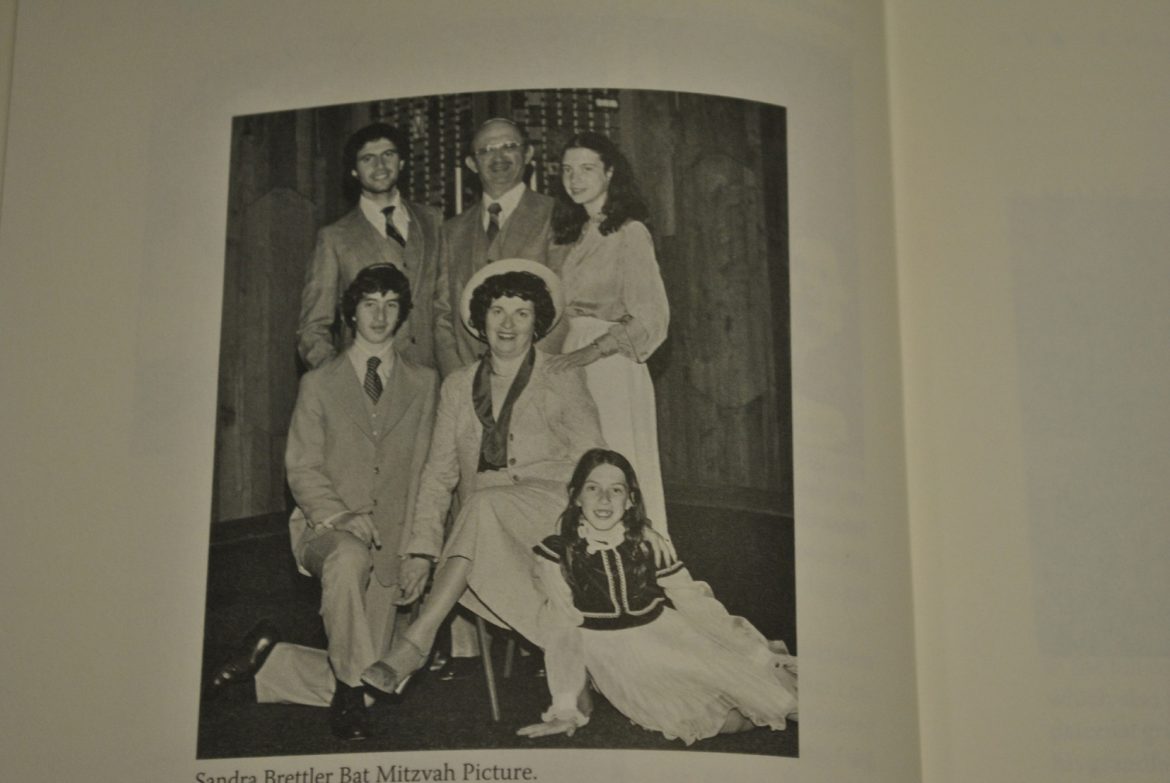

Brettler then got married, had four children, and joined a support group for child holocaust survivors.

“I ask you not to be silent observers when you see injustice happening around you,” Brettler said to students.

Sociology professor Helen Dosik, said she invited Brettler to speak to her sociology class because her story is an example of the many people that have been neglected.

“It is very important to emphasize that she is a child survivor,” Dosik said. “Child survivor stories were often neglected because a lot of the focus at the time was on the adults.”

Katie Swanson, a history major, said she has attended three of Brettler’s lectures.

“I love being able to hear Eva’s story firsthand,” Swanson said. “It’s so incredible. It’s so prevalent with all the anti-Semitism that has been happening all over the world. Discrimination is still an issue that is happening today.”