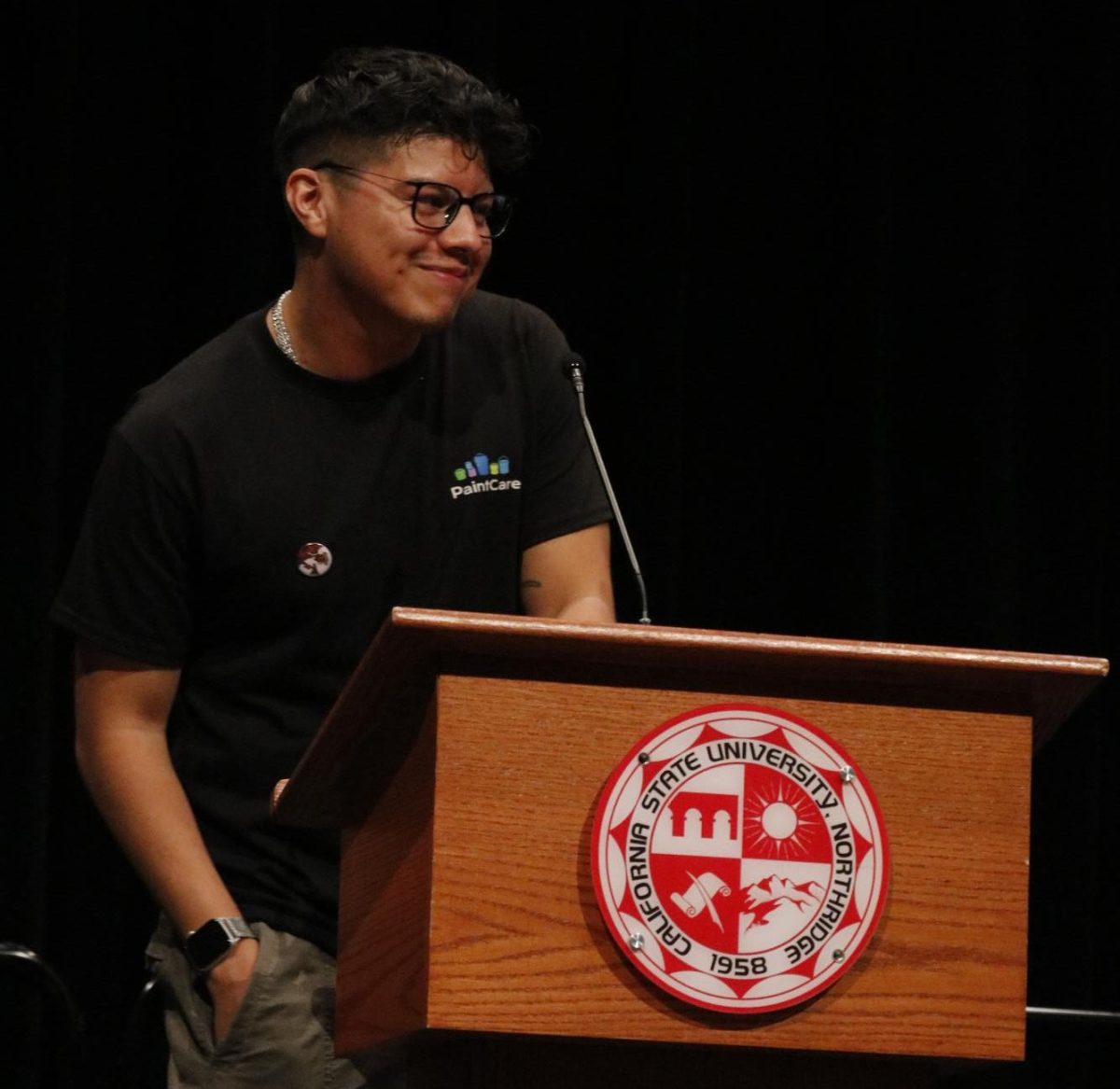

CSUN student Ronnie Veliz, 34, knew they were different since they were 4 years old.

“When I was a little kid, I remember breaking so many gender norms and would often get in trouble for it,” said Veliz, who was assigned male at birth but identifies as gender non-binary.

Veliz is from Trujillo, Peru, a small town where the only mention of the LGBTQ+ community was of gay men during the AIDS epidemic. In fact, Veliz did not realize that there were more members of this community, including those who are gender non-binary, until they moved to the United States after being kicked out by their father for coming out as gay.

When they first moved to the U.S., Veliz was homeless for nine months because they were afraid of reaching out to a social worker.

“I didn’t feel like I could reach out to these people, because I was worried they wouldn’t relate to me,” they said.

According to the U.S. census, women make up 80 percent of social workers in the United States, and 67 percent of all people in this occupation are white.

“I worry about the same dynamic, and it’s true that the history of social work is very white, cisgender and female,” said Katie Mortimer, the executive director of field education, contracts and admissions in the social work department of CSUN. “Our Master of Social Work (MSW) program is especially trying to reach out to more diverse, vulnerable people who represent the communities we’re trying to help.”

However, Sonya Keith said, a program operations supervisor at Tarzana Treatment Center, social workers have to meet certain professional standards, which include cultural competency.

“Learning that not everyone has the same power struggles and privilege that I do helped me open up to what someone is really living — not what I assume they experience because of what I know,” said Keith.

Keith further expressed the emotional intelligence required in her field.

“Thinking like a social worker is different than thinking like somebody’s friend,” added Keith. “I openly judge my friends because we have already established that I value them. Social work is different.”

Veliz is now training to be a social worker in CSUN’s MSW program.

“I want to create the first organization in the Valley that is run by and helps people who are LGBTQ+, immigrants and people with disabilities,” Veliz said.

When Veliz started CSUN as a psychology major in 2011 they created a club called Matadors for Equality (MFE) which they described as “a safe space for immigrants, the LGBTQ+ community and those with disabilities to discuss their similarities, not their differences.”

MFE won the 2012-2013 Matador Involvement Center Commitment to Social Justice Award. Veliz received their B.A. in psychology in 2012, and graduated with honors.

However, it took Veliz most of their college years to figure out their gender identity.

“I had to wait until college to know there were lesbians and trans people too, but it took me longer to accept who I was,” they said. “I was so hungry for knowledge to find out my gender and sexuality.”

In 2017 Veliz came out as non-binary.

“I thought it would be easier, but it wasn’t,” they said.

Despite the legalization of same-sex marriage in the United States in 2015 and overall increase of acceptance of the LGBTQ+ community in the United States, a memo leaked in October implied that the Trump administration wanted to define gender only by the genitalia someone is born with and nothing else.

“It took us so long for the country to accept us, and now the president wants to eliminate us,” said Veliz. “There are not many role models who are are trans and non-binary. What did we do to you?”