Students graduating from the Los Angeles Unified School District are under-prepared for their first year of college, experts say, pointing to lowered graduation requirements, questionable online credit recovery courses and incomplete intervention as the culprits.

To meet a college and career readiness plan, LAUSD began aligning the graduation requirements with the basic requirements to apply to a University of California or California State University school. Later on, funds were approved to intervene when a student was falling behind on their credits through recovery courses. The primary motive for this was to increase the graduation rates.

For the graduating class of 2016, LAUSD re-implemented an “A-G” set of course requirements, previously introduced in 2005, that aligned with CSU admission requirements. Students would take a set amount of years in math, lab science, history, English and other subjects. For a student to receive a high school diploma they must meet the minimum A-G courses, California Department of Education standards and other LAUSD requirements.

That same year, however, the passing grade standard of a “C” was replaced with a “D” for A-G courses to get more students to graduate.

“Standards lowered in A-G in LAUSD to get students to graduate and go to college, you can see the irony,” Russell Rumberger, director of California Research Dropout Project, said.

Ford Roosevelt, director of Project GRAD, explained that LAUSD lowered the requirements to a “D” because so many students were failing. But students who received the diploma with a “D” were not prepared for college and most of them ended up taking remedial courses in math and English, he said.

Rumberger also explained that depending on how well a student does in high school is a basic predictor of how they’ll do in college.

“If there’s watered-down curriculum in high school and watered-down curriculum in credit recovery, it’s not enough,” he said.

A high school student behind in credits in core subjects of math, science, language arts and social sciences is required to take a credit recovery course to make up for missing credits to graduate.

In 2017, Title I funds were reallocated to the CORE High School Credit Recovery/Intervention Program, providing opportunities for students to retake classes in core subjects. Students at risk of not meeting “grade level standards” and graduation requirements were recommended to take CORE Credit Recovery.

Credit recovery courses can be taken in different forms, such as an after school class offered at adult school, online, or blended where the content is offered online but students meet with an LAUSD instructor.

In a 2016 study conducted by American Institutes for Research (AIR), researchers from AIR and University of Chicago were studying the efficacy of credit recovery courses for Algebra 1 through online and “face-to-face.” Their research found that both models failed to improve students’ general comprehension of the content or their assessment scores on the subject.

Rumberger says that online credit recovery has potential, but it is still questionable whether the content is rigorous enough for students to receive the material well.

Vanessa De Leon, an A-G diploma counselor from John Marshall High School, works with students at risk of dropping out. She says that most students who take credit recovery courses would otherwise be dropping out and are not UC/CSU bound after graduating. Instead, they take the community college route first.

De Leon said that while online credit recovery courses may not be providing the skills for students to be successful, “If we didn’t have these opportunities, there would be a high number of students not graduating.”

AIR will be conducting another research on blended learning versus online. Yet as the debate continues on the resourcefulness of these intervention programs, there’s still intervention missing in some areas.

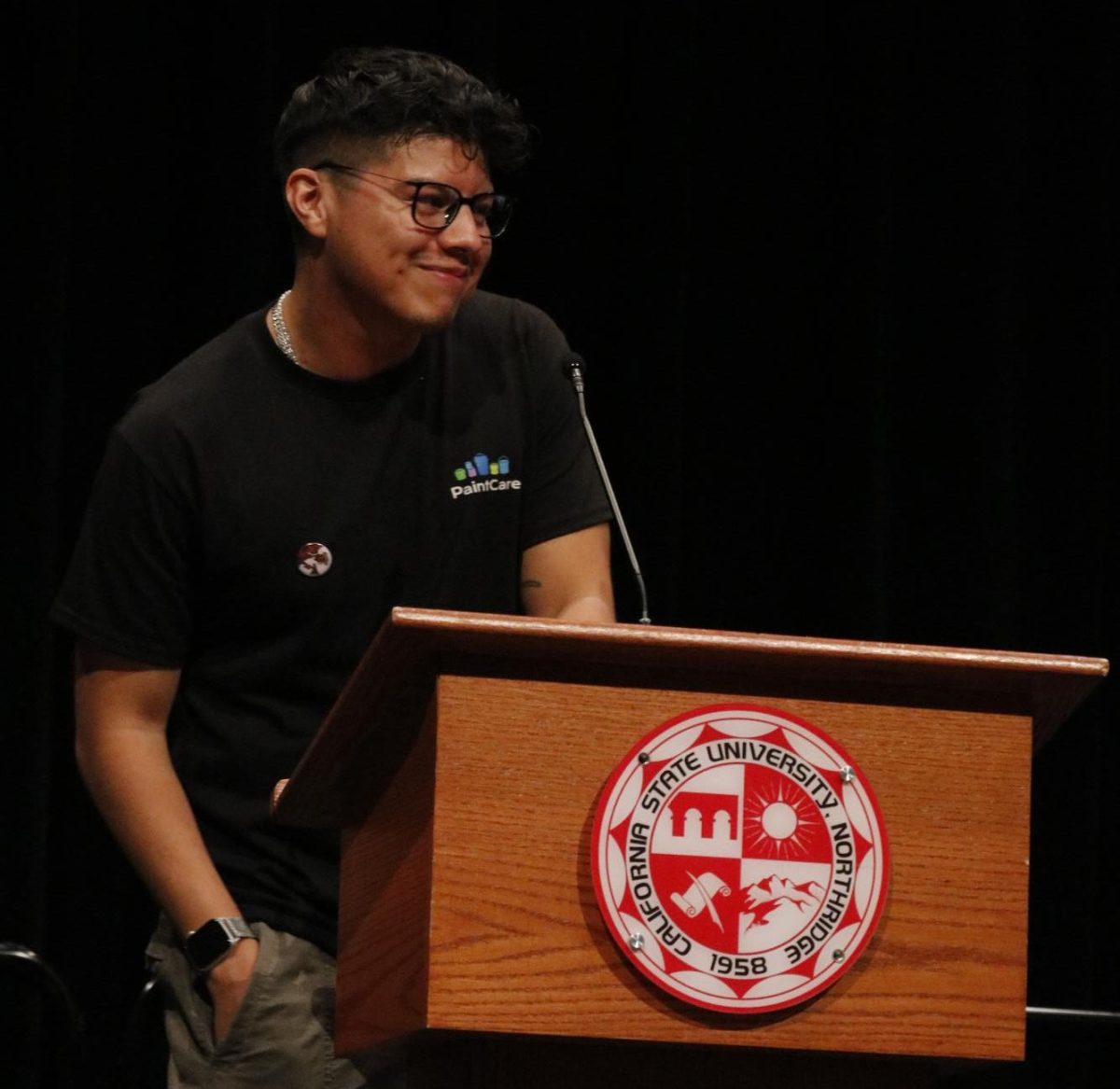

Jack Bagwell, assistant professor at CSUN and former elementary school assistant principal for LAUSD, says that there needs to be more intervention on a social/emotional level for students to really learn.

“The state needs to provide more human and health services,” he said, as well as create more partnerships with community organizations that will assist in these fields. Not every elementary school has a full-time nurse, a psychiatrist or a therapist, Bagwell said.

De Leon talked about her experience as a middle school counselor, where most of the time she dealt with student behavior, getting them to feel safe and grounded to sit in class because they come in with a myriad of issues. There needs to be more intervention at a middle school and elementary level, she said, “For the future of students and the future of LAUSD.”

Roosevelt says that as a former teacher, they need to be better at recognizing what is challenging students and preventing them from focusing inside the classroom. He points out that many students from LAUSD are first generation and are from low-income communities.

“How do we address those reasons as a community, as faculty, as teachers?” he said. “It’s tough.”

Kelly Gonez, member of the LAUSD Board of Education for East San Fernando Valley, wrote in an email that not every high school has a college counselor, that many schools make up for the gaps through online resources and staff, but these gaps are due to budgetary constraints.

She added that LAUSD needs to make sure more students pass their classes the first time rather than rely on credit recovery.

Gonez wrote that LAUSD is “acknowledging that it’s not enough to see our students to high school graduation. We have to make sure they graduate prepared for success in college and in a career.”