It was like a horror movie.

One minute she’d be extremely sweet and loving. The next minute she would become incredibly violent. And without any memory of what had just happened, she’d be fine once again.

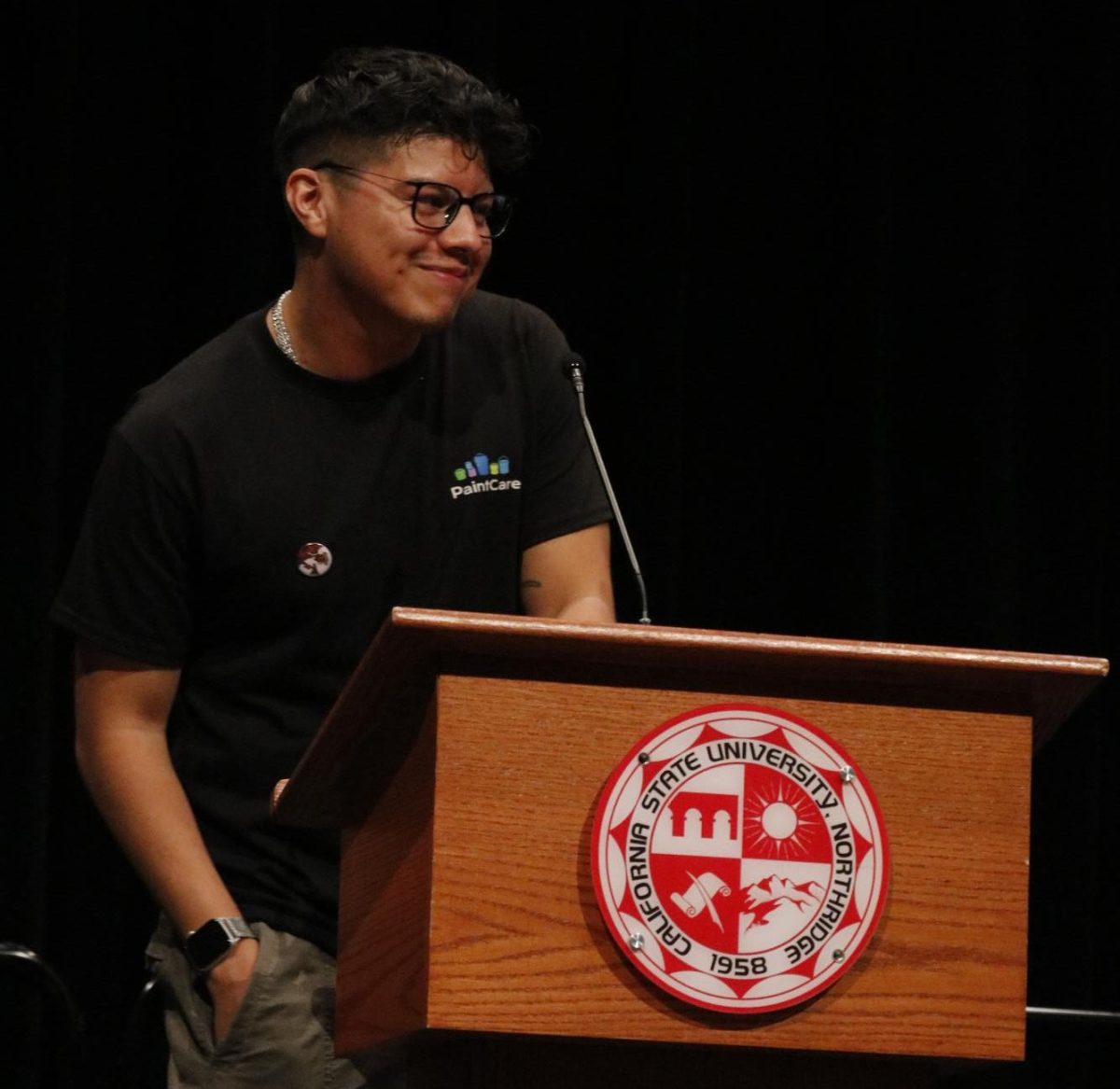

Michael Schofield, an English department lecturer at CSUN, and his wife first took their daughter, Jani, to a child psychiatrist at the age of 5 to diagnose the cause behind such unexplainable behavior.

By 2009 at the age of 6, Jani was diagnosed with child onset schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is most common in men and women from the ages of 18 to 25, according to medicinenet.com. Only one in 40,000 children are diagnosed with schizophrenia compared to one in 100 adults.

Jani would have several episodes a day. And it only became worse when her brother, Bodhi, was born and she attempted to harm him. Other times, she would try to harm herself. Schofield recalled once putting Jani on a timeout only to walk into her room later and see her trying to strangle herself.

“All of a sudden, it was like she was possessed,” Schofield said. “Except it was biological.”

In addition to her violent behavior, Jani experienced hallucinations.

What Schofield and his wife assumed were just imaginary friends to Jani were some of the hallucinations driving her to do the things she did. One hallucination was of a vicious cat named 400 that told her he’d bite and scratch her if she didn’t hurt someone.

Although there is no cure for schizophrenia, Jani is given medication to manage her hallucinations. Clozapine has proven to be the most beneficial for her, Schofield said. However, with such strong medication comes serious side effects, including changes in blood sugar, cholesterol, and a decrease in white blood cell count. For these reasons, Jani must have her blood tested on a monthly basis to monitor her bodily functions.

Now 12 years old, Jani has come a far way. With less episodes and a better grasp on her world, she has her own friends, goes to school, and is a normal 12-year-old girl, Schofield said.

“I’m extremely proud of her,” Schofield said. “She lost a big chunk of her childhood. But she fights it everyday and she wins most of the time. She’s happy.”

Schofield has also learned to embrace the situation, using it as a chance to educate the public on schizophrenia and mental health. Most people know the terms but don’t know what they really mean unless they have first-hand experience, Schofield said.

In 2012, Schofield and his wife founded a nonprofit organization, the Jani Foundation, providing children with mental disorders and their parents with a safe haven to socialize and a judge-free community. The foundation holds events like go-karting and halloween parties, giving the children a chance to socialize. The group now consists of about 60 children.

“At the events, parents never have to apologize if their child has an episode,” Schofield said. “We wanted to show people that they aren’t alone and they have a support system. We even offer an online support group.”

The next step Schofield took in educating the world on mental health was publishing his book, “January First: A Child’s Descent into Madness and Her Father’s Struggle to Save Her,” in August 2012.

Schofield and his family were already in the media spotlight after a front page story in the LA Times, so he didn’t see the reason to hide Jani’s struggle any longer. Instead, he saw it as an opportunity to make sure Jani would be accepted instead of feared or hated by the world.

“It isn’t their fault that children like Jani are betrayed by their own mind,” Schofield said. “They deserve the same happiness.”

Since most mental health issues strike in the college years, Schofield emphasized the importance for our society to keep a close eye on loved ones and friends, especially on campus. If a friend is going through a radical personality change, it should be taken seriously, Schofield said.

“As a society and as a university, we have to stop ourselves from saying, ‘That person is just weird,’” Schofield said. “Because it could be the beginning of a serious disease and you could save a life.”

The future is still unknown for Jani and her family but they are taking it a day at a time. Even though they haven’t erased Jani’s schizophrenia, they have stopped it from advancing.

The ultimate goal: keeping Jani alive and giving her as many moments of happiness as they can, Schofield said.

Check out the rest of The Sundial’s Mental Health Issue in a special section here.