[This story has been updated with the following corrections: Ravensbrück concentration camp has been changed from Robinsbrook concentration camp; Eva Brettler’s name has been changed from Eva Katz in the photo caption.]

Three Holocaust survivors shared their stories with CSUN students Monday in a panel discussion led by Religious Studies professor Dr. Beth Cohen.

“It really challenges our imagination to think about six million Jews murdered,” said Cohen, who coordinates the event to coincide with her class, The Holocaust: Religious Responses. “Hearing these stories helps to personalize the statistics.”

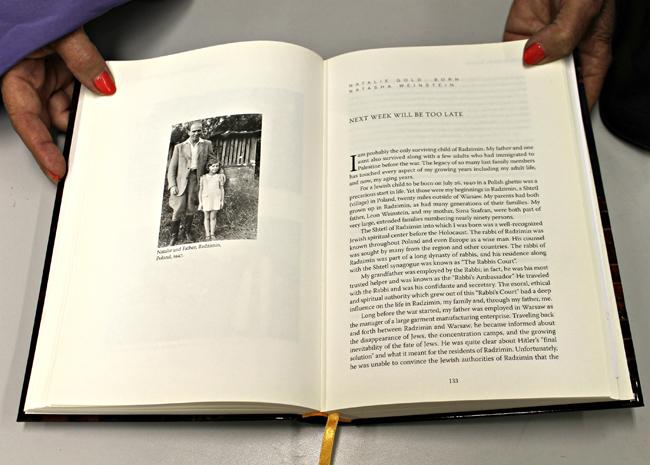

Eva Brettler, Natalie Gold and Harry Davids spoke about their unique childhoods and ultimate survival during the Holocaust, which claimed about 250 immediate family members between the three of them.

“I hope you will understand the Holocaust wasn’t a monolithic experience,” said Cohen. “The effects are not the same for every victim.”

Gold told students that her parents left her on a doorstep at only 18 months old with a note for the finder to save her, fearing that keeping her would mean death.

Gold ended up in a convent, passed off as a Christian. Most of her family ended up as casualties of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the largest revolt by Jews in WWII.

“People are just beginning to understand the impact of war,” said Gold. “Trauma is a multi-generational event.”

Senior Johnny Gomez, who is writing a paper on civil injustice, said he attended this particular event because it has deep meaning for his family, who stays connected by studying together.

“People that go through extreme trauma like that generally have a better outlook on life, which is a beautiful thing,” said Gomez.

Gold explained that there are currently newcomers to the U.S. of different backgrounds and people can use the same compassion toward them.

“All three of us are here because of the help of others,” said Gold. “So, in turn, we help.”

Gold, a therapist and social worker herself, said that 60 to 70 percent of Holocaust child survivors are in positions where they help others and she doesn’t think that’s an accident.

“One of my missions in life is to make ‘upstanders’ instead of bystanders,” said Davids, who also occasionally works at the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust. Davids explained that too many people remained idle in a horrific situation and we have to learn from history.

Davids was a very sick infant who was given to a Dutch family that only knew his first name and that he was Jewish. The family decided as Christians they would not let anyone die, even though they were already a family of six.

Davids said that most people are unaware that Holland had the second-highest Nazi support behind Germany itself, which means that the family sacrificed immensely to hide a Jewish child.

Davids was eventually tracked down by an uncle from South Africa and adopted, although the process was long and tedious. Not only did Davids’ Dutch family not want to release him because they considered him family, but Davids also didn’t have citizenship for travel.

“In those days, some didn’t have documents and some had altered documents,” Gold said.

Gold explained “name-Nazification,” where officials often added the names Sara or Israel to government records so a person’s Jewish origin could always be traced, making it harder to hide.

“Jews have always been suspicious of official documents,” said Gold. “They were never used to help us. Only to harm us”

Gold explained that her father kept her off any list since birth, but that may have saved her life.

“I don’t exist,” said Gold. “I don’t have a birth certificate. But that was really smart of my father.”

Gold did admit that she has had bonding issues throughout her life, perhaps because of a hushed identity, and perhaps from being “jostled around” in her early years.

One bond that has benefit Gold is the Holocaust child survivor group where the three speakers met years ago.

“It’s a very, very special connection,” said Brettler, the only speaker who said she is old enough to have full memory of her experience.

Brettler said that all of the Holocaust survivors must speak for those who are not alive to speak for themselves.

Originally from Transylvania, Brettler was among a group who marched to Ravensbrück concentration camp with her mother, who never arrived at the end destination.

“They stripped us, they shaved my hair, they ordered us to give up all personal possessions,“ said Brettler, who kept her only belonging, a ring from her seventh birthday, under her tongue.

“I was so desperate to have something that connected me to my past,” said Brettler.

She was later moved to another camp where she described “mountains of corpses.” Brettler said that no one bothered to bury the Jewish bodies.

On April 14, 1945, Brettler recalled sneaking outside the barracks to get some sunlight when a teary-eyed British soldier gave her a chocolate bar. The war had ended and she was alive.

Freshman Melissa Ohana said she attended this panel after hearing Brettler speak previously last April.

Ohana said Brettler inspired her to take a class trip to Poland and Israel, visit many of the places mentioned, and see where she comes from.

“I’m looking at you and I’m hoping you’ll be my future ambassadors,” said Brettler to the students. “It cannot be forgotten.”

Toward the end of the event, Cohen asked the panelists why they waited so long to tell their stories.

“We were always told don’t talk about it and it won’t hurt you, “ said Brettler.

Cohen said that for most of the Holocaust survivors she has interviewed, their war started when the war ended.

Davids said that his adopted father came to hate everything German and he carried that with him throughout his life.

“In some ways, the Nazis beat him twice,” said Davids. “Hatred is a terrible beast in any form. My answer is to live your life. That’s the best revenge.”