Technology-driven jobs in engineering and computer science are providing more than 80 percent of all employment in science, technology, engineering and mathematics fields, according to a 2013 survey report by the US Census.

However, women don’t reflect the ever-growing workforce.

Although women make up nearly half of the working population, according to the survey, they remain underrepresented in the thriving field of technology.

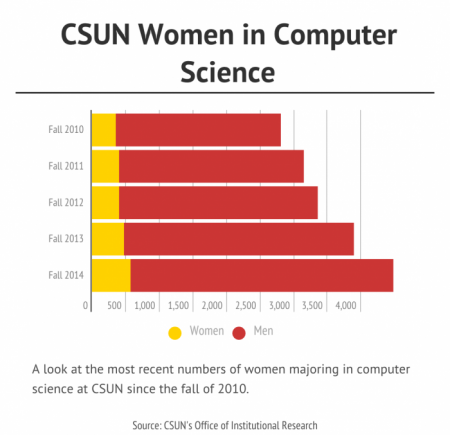

According to CSUN’s Office of Institutional Research, in fall 2014, only 577 women out of 4,484, 12.9 percent, majored in the engineering and computer science department.

The stark gender divide between students mirrors the professional workforce. Out of a total of 23 full-time faculty at the engineering and computer science department at CSUN, six are women.

Computer Science Professor Ani Nahapetian said that part of the reason fewer women may be inclined to enter the field is due to the lack of computer science programs in high schools.

“A theory that rings true to me is that we aren’t typically exposed to computer science in high school,” Nahapetian said. “Women coming to computer science brand new can be intimidated in college, especially in a classroom full of men who have tampered with it or know the jargon better.”

In an effort to match the growing field of technology, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio most recently announced that, within 10 years, all of the city’s public schools will be required to offer computer science to students, according to New York City’s official website.

Other cities already in the process of integrating computer science in their public schools’ curriculum include Chicago with a five-year plan, and according to the Los Angeles Unified School District, Los Angeles who teamed up with Code.org, a Seattle based non-profit organization.

The implication that women are more likely to major in classes they took in high school means that confidence, rather than aptitude or interest, is a determining factor in choosing a career in computer science, according to Diana Franklin’s book “A Practical Guide to Gender Diversity for Computer Science Faculty.”

CSUN computer science major, Kimberly Rosas de Almida, 19, is drawn to programming through her middle school robotics club.

“I learned how to program legos with sim cards, which is how we raced our robots,” Rosas de Almida said. “I really liked it and that’s what got me into programming.”

Apart from early education, CSUN Computer Science Professor Wen Chin Hsu said that parental influences play a role in a child’s interest in computers.

“Computers were once considered toys and, in the past, parents linked them to ‘boy toys’ when they bought gifts for their kids,” Chin Hsu said. “When girls don’t have that kind of childhood experience, they may intend to explore other fields, which could lead to less interests in the computer science field.”

Chanya Dudley, 19, a female computer science major at CSUN, attests to the similar conventions placed on programmers.

“The stereotype is that computer science people are just introverted nerds who code all day and night, only wear hoodies and t-shirts,” Dudley said. “But people need to learn that you can be a girl, wear skirts, lipstick, high-heels and still be into computers.”

Dudley finds that about 80 percent of her male classmates are helpful and supportive while the rest think the only science in which girls should be involved is biology.

“It can be intimidating being one of the three girls in a class filled with 27 males,” Dudley said. “Not to mention, some of the males have been programming since high school, which can make me feel inadequate at times.”

The disproportion of women to men in classrooms is an issue that is carried into the workforce.

UCLA graduate Bridget Dickens, a former pool-installation programmer, worked 11 years at a company that didn’t value her seniority or programming skills while entry-level males received the support and mentorship she was being denied.

“They were hiring males who didn’t know what they were doing, and the company was preparing them for better positions, when I had been there longer and wanted to move up,” Dickens said. “When I reached out for that kind of support, and [showed] interest in advancement, I was [asked] ‘why’ by the director of engineers who had me doing administrative work.”

Dickens’ experience reflects a larger trend of how women are at a disadvantage in male-dominated groups.

A 2004 study from Boise State University found that when women are the tokens in a working group, they are more likely to have their mistakes amplified, be socially isolated and be found in roles that undermine their status.

After 11 years of repeated discrimination, Dickens quit.

“Other women should know their value when a manager is messing around and know it’s best to leave,” said Dickens who attended an event hosted by Women Who Code LA, an organization of women interested in engineering and computer science. “I’m here to learn more about programming and provide myself with better opportunities.”