Vaccine hesitancy stands in the way of reducing COVID-19 cases in communities of color

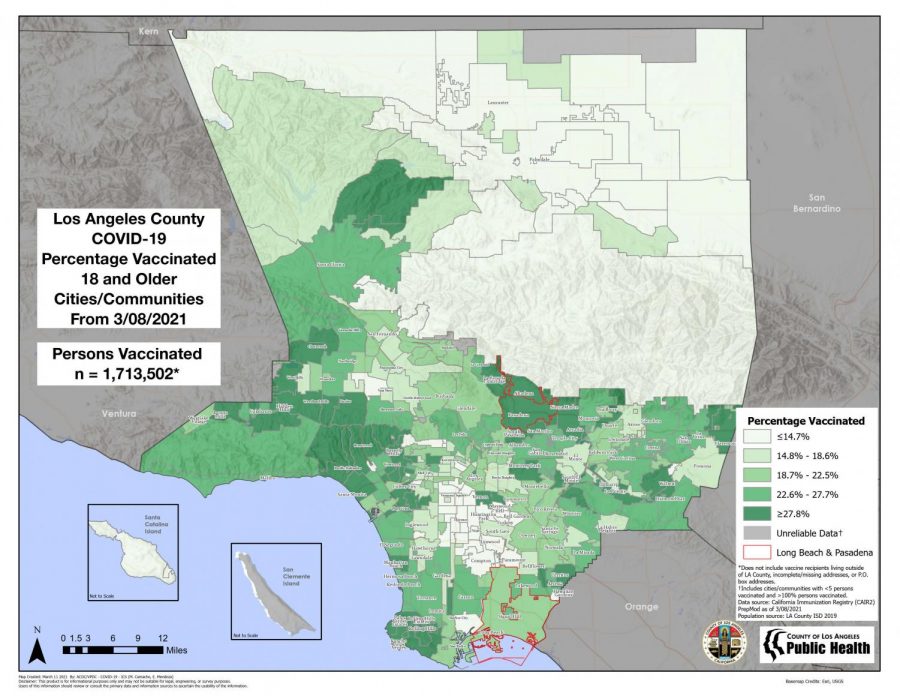

Los Angeles County Public Health Department

The chart highlights the disproportionate vaccine distribution in Los Angeles County. Low-income neighborhoods, populated by communities of color, have a lower percentage of vaccinated persons.

March 26, 2021

COVID-19 continues to disproportionately impact communities of color in low-income neighborhoods throughout Los Angeles County, and the communities’ hesitancy toward getting the vaccine threatens to perpetuate the problem.

The infection rate for households with an income of less than $40,000 is more than double that of those with an income of $120,000 or more, according to Gov. Gavin Newsom’s press release March 4.

Vaccination rates in wealthier neighborhoods such as Brentwood, Encino, and Culver City are more than double those in lower-income neighborhoods, according to L.A. County Public Health Department data.

In California’s most recent plan to correct vaccine inequity, officials enacted a new policy that allows 40% of Johnson & Johnson vaccines to be set aside for those who are most vulnerable, according to the equity plan’s fact sheet.

“Once we get that 40% … we will open up certain sites that will inoculate in Johnson & Johnson. Because some people are hesitant about one vaccine over another, we are going to set up different sites for different people based on the brand they want,” said Kenichi Haskett, section chief of L.A. County Fire Department.

For some, this opportunity will be lost to vaccine hesitancy, which can stem from distrust in the public healthcare system, misinformation, safety concerns and complex individual deliberation.

African Americans and Latinos are cited as being the most unsure about getting vaccinated, according to a state survey by the Public Policy Institute in California.

“Unfortunately, certain demographics in our county, our harder hit, more vulnerable populations, there are some myths there. Some populations don’t want to be vaccinated because of societal fears or unknowns. We are trying to get mobile clinics into those communities who are able to speak facts about the vaccine,” said Haskett.

Historical medical mistreatment toward people of color, such as the Tuskegee Experiment and the sterilization of Mexican immigrant women, is a reason for the the African American and Latino communities’ distrust toward the healthcare system.

However, it’s also the passive-aggressive racism — also known as microaggressions — in the actions and communication within the healthcare system today that fuels the communities’ distrust, said Dr. Melissa Clarke during a webinar.

An example of a microaggression’s effect is a lower number of referrals for life-saving treatment for people of color compared to white people, according to Clarke, a Kaiser Permanente emergency medical physician and co-founder of the non-profit organization Black Coalition Against COVID-19.

A recent study on physician’s racial microaggressions toward patients found that race shapes physician-patient interactions in medical practice, including a doctor’s response to emotional expressions, treatment recommendations, and bringing up the subject of race. The study showed these practices typically work to the disadvantage of people of color.

“Disempowerment breeds mistrust,” said Clarke.

Another factor in vaccine deliberation is the rapid development and rollout process that the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines went through, which escalated safety concerns. The vaccines were given Emergency Use Authorization in December by the Food and Drug Administration causing many who have taken the PPIC survey on vaccine responses to cite that they want to “wait and see” what happens.

“[Waiting to see] prolongs our return to normal,” according to Haskett, who suggested paying attention to fact-based medical studies when deliberating a vaccine.

“I’ve met people who are hesitant, then after they get vaccinated, they’re excited that they did it,” said Manuel Martinez, CSUN’s public information officer for their vaccine site. “We want to remind people it’s safe and that it’s the best way to overcome the pandemic and get everything back to normal.”