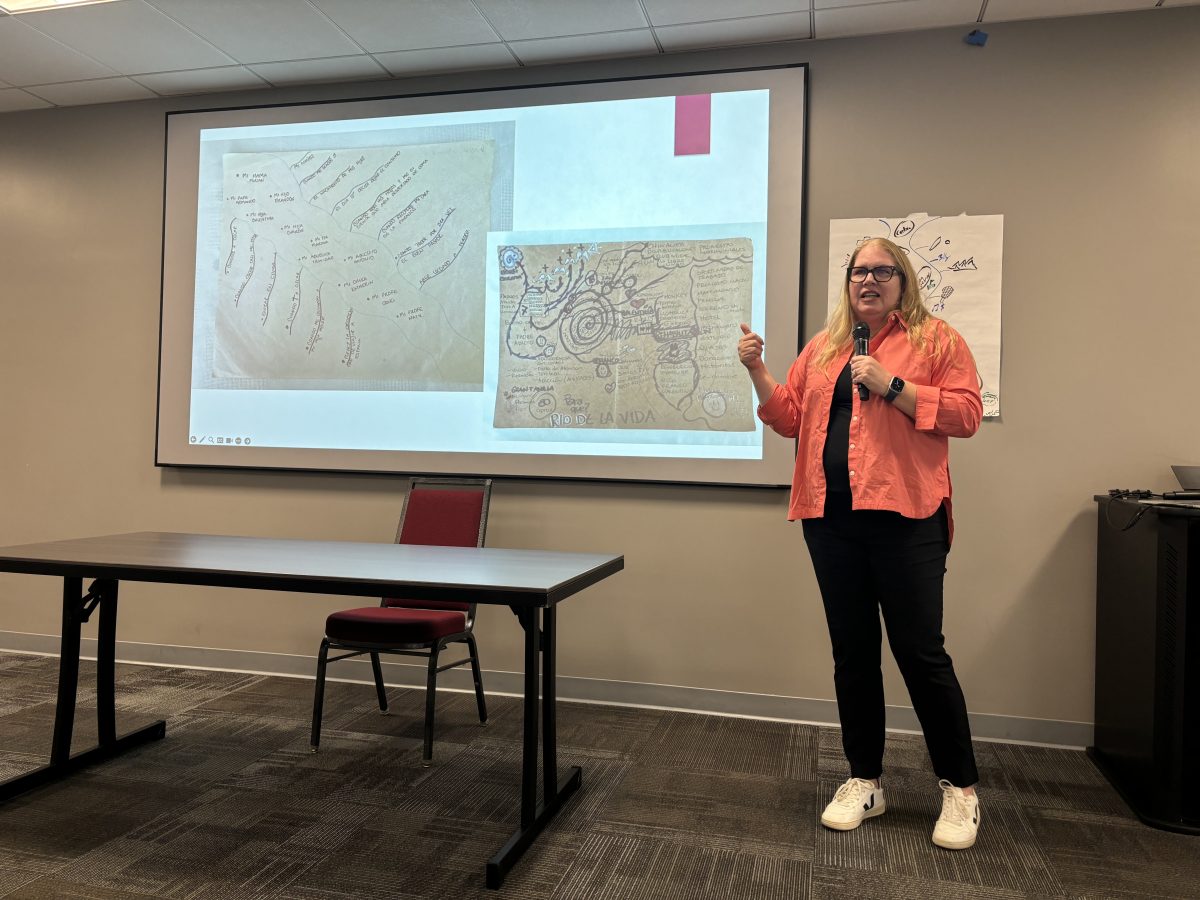

Political science professor Jane Bayes remembers seeing FBI agents with their guns drawn at what was then known as San Fernando Valley State College. Students at San Fernando Valley State, like many colleges across America, were protesting to demand the establishment of ethnic studies on campus.

“They were arresting anybody of color? — any (physical) body of color was being arrested by the police,” Bayes said. She described hiding students in cars and sneaking them off campus.

It was 1968 and Bayes was lecturing on minority politics to Chicano, black and white students in Sierra Hall. She approached her class like an organizer, inviting black and Chicano “freedom fighters” to talk to her students, many of whom were activists themselves.

Bayes, now 79, recalls her classrooms becoming more than just a lecture hall as students cried out in frustration about the lack of opportunity and social injustice that was happening on campus during the civil rights movement.

Her students were so passionate that her classes often ended in shouting matches. It would get so bad that Bayes would have to decompress from the tension.

“On the weekends I had to go in the ocean and wash it all off,” she explained. “My students would be running into class and looking in the windows to see if the police were in Sierra Hall — you know the windows are a little high — and they were standing and (looking) up to see if the FBI were around and who was going to come to arrest them.”

It’s been 50 years since black and Chicano students came together to demonstrate for greater diversity on campus. Today, CSUN is one of the most diverse campuses in America, with nearly half of its student body identifying as Hispanic/Latino.

But today, proposals like Executive Order 1100 has Bayes wondering if the struggle for ethnic studies is still not done. “We need to be leaders of the system, not the ones to be considered the outcast,” she said.

Bayes’s political awakening began through the influence of her mother as she was growing up in Texas. She recalled long conversations with her mother about segregation, but Bayes’s involvement in the movements for civil and women’s rights issues didn’t take over her life until she finished her Ph.D. at UCLA in 1967 and was hired to teach in political science at CSUN. Eventually her activist students asked her to make speeches.

“I was a little afraid … I wasn’t born to do this, but it was a decision you had to make,” Bayes said. “You were either for it or against it. If you’re for it, you better stand up and do it, so I went out and made a speech.”

Bayes found herself at the center of the battle for ethnic studies because her students were activists, such as Archie Chapman, president of the Black Student Union.

“There were very few,” she said, speaking about the students protesting in 1968. “(But) it was a very active group.”

Bayes said that the students now have a lot of experience, not only because some students that protested last year are coming back to protest, but because most of the students are ethnically diverse.

“They’re very articulate of what it means to them,” said Bayes.

During her first years at CSUN, Bayes said that the battle for social justice and civil rights mattered more than a paycheck.

She went on to become one of the first female professors at CSUN to hold tenure and today she teaches classes about the politics of globalization, gender and democratization.

Bayes is highly involved in the women’s rights movements both on CSUN’s campus and in Los Angeles. Her involvement includes being a part of the International Social Science Council, and she was one of the representatives for the International Political Science Association at the UN Commission meeting on the Status of Women in Beijing in 1995.

She is currently active in the League of Women Voters human trafficking committee and is part of a study group in the LA County commission on human trafficking. In the late 1980s, Bayes became one of the first women to become a president of the Western region for the American Political Science Association.

In regards to keeping education ethnically diverse, Bayes knows the struggle it has been to keep Section F on campus.

“It’s taken 50 years — 50 years! — to build these departments up,” she said.

Bayes believes that she sees a lot of similarities between what students were trying to accomplish in 1968 and what students are trying to do today as they demonstrate against Executive Order 1100.

Bayes says that the administration hasn’t taken into account the problem of student schedules.

“They don’t take into account the fact that most of you work, full-time some? — ?most — people do school on top of that,” she said. “Getting through CSUN in four years is only possible if you’re fully funded.”

Bayes fears that if Executive Order 1100 is implemented at CSUN, departments like Chicana/o Studies, Africana Studies, Asian American Studies, Queer Studies, and Gender and Women Studies could lose faculty since their enrollments depend on the number of students enrolled in courses that are under cultural studies. Executive Order 1100 will then allow double counting GE courses from different sections, which can decrease cultural studies enrollment, Bayes said.

She said that white European history has been taught in schools for decades. Having ethnic studies on campus can help keep diversity strong on CSU campuses.

“(Ethnic) courses serve a big purpose to the people who don’t know their own history,” said Bayes. “It’s just plain ignorant to ignore it.”

Bayes reflected on the campus 50 years ago. It was a different time and while students were fighting for civil and social rights, the fear of being drafted to fight in the Vietnam War was also a concern, but she sees the same passion to fight for ethnic studies in the students today.

She recalled people who have left a huge impact on the CSUN campus such as Archie Chapman and Rudy Acuna, professor and activist in the Chicana/o Studies Department.

There’s a moral cause behind the fight against Executive Order 1100 and part of it is the continuation of the civil rights movement to have freedom to get a good education. “The students want these courses and are asking (for them),” Bayes explained.

She doesn’t feel that President Dianne F. Harrison is showing much of interest on the topic. “She didn’t come to the meeting,” Bayes said, referring to Thursday’s meeting with the Faculty Senate. “She’s in a hard place herself, but she’s the president, stand up and fight!”